Have you ever wondered why the chemical symbol for sodium is Na? Or why humans are known as Homo sapiens? This two-parter article answers these questions and more by analysing the etymology of modern scientific classification systems.

An Exploration into Chemistry and Biology Etymology

Language Edition | Etymology| Cindy Yi & Jasmine Gunton

Unusual Chemical Naming and Chemical Element Etymology

Hg is my favourite element beginning with ‘m.’

While the beginning stages of the modern periodic table were invented as recently as 1869 by Dmitri Mendeleev [1], many chemical elements have been independently discovered, and named, for millennia. The structure and order of the periodic table, however, has not always been reflected in the naming.

The naming of chemical elements is not just a scientific matter, but a historical one. Although the principles of scientific reasoning, observation, and logic are universal, the nature of language and the very human characteristic of bias has led us to relate to things – and elements – we observe with varying degrees of ‘correctness.’ And so, while the origins of many element names may no longer be considered chemically accurate, some have become engrained and remain in chemical nomenclature. The languages from which we derive our ‘official’ periodic names are numerous, and their reasons for naming are abundant; however, this essay will focus on a few unusual names of interests and their various roots and stories.

Mercury - Hg

Mercury may be the best known unusually abbreviated element. Neither ‘H’ nor ‘g’ are in the word ‘mercury’, but the chemical symbol in fact pays homage to the origins of the element’s written history. Mercury is one of the oldest known elements, having been known in Egypt and probably parts of Asia from as early as 1500 BCE [2]. It is a shimmery, silver-coloured metal, well-known for being the only liquid metal at room temperature. The symbol ‘Hg’ was from the initial Latin characterisation of the mercury obtained from cinnabar as hydragyrum [3], which itself has Greek origins from the words hydor and argyros, meaning ‘water-silver.’

Mercury later also became known as argentum vivum when in its liquid elemental state, literally ‘living silver’ [3]. Anglicized to ‘quicksilver,’ known in Middle English as quikselver and Old English as the barely recognisable cwicseolfor, mercury is still known in many other languages as cognates such as the Dutch kwikzilver, German Quecksilber and the Swedish kvicksilver. So, while quicksilver is still a relatively common name in other Germanic languages, why has modern English deviated to using ‘mercury’?

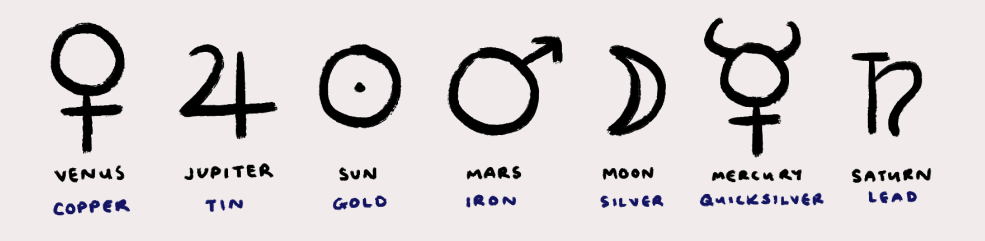

The answer lies in alchemy. Ancient humankind linked the seven known metals to the seven celestial bodies, and the perceived relationship between the metals and the planets was reflected in the practices of alchemy and astrology in the Middle Ages [4]. Some connections are more obvious than others – gold was associated with the yellow sun, and silver with the silver moon. The rust-red of Mars mirrored the red rust of iron; lead, being a heavy metal, was associated with the sluggish orbit of Saturn, perceived to be a ‘heavier’ planet due to its longer orbit time.

Quicksilver’s fluidity and mobility earned its title of Mercury, the quick-footed Roman god of messengers and thieves. While the alchemical assignments for other metals have all but faded away along with alchemy itself, mercury bears its planetary name* to this day. Antoine Lavoisier et al.’s book Méthode de nomenclature chimique, published in 1787, proposed the new nomenclature of chemical substances, providing a foundation for the progress of modern chemistry [5]. In the Méthode, the authors corrected many alchemical names, with the exception of mercure – and so, the name mercury has stuck.

Figure 1. The planetary alchemical symbols. Illustration by Cindy Yi.

Potassium - K

While some elements were assigned names based on their characteristics, much like mercury above, others have names derived from their derivation and use. Potassium is one such element – the name potassium comes from the word ‘potash,’ referring to early methods of potassium salt extraction; the ash of burnt wood and tree leaves would be placed in a pot, water added, and heat applied to evaporate the solution [6]. The suffix -ium is common for most metals (calcium, magnesium, palladium, cadmium, etc.) and thus the name potassium was born.

But why the chemical symbol K? Surely P (phosphorus won that one), Po (sorry, taken by polonium!) or even Ps (that one’s free) would make more sense?

While you’d be forgiven for thinking Latin was the culprit, as it has been in numerous cases (Au - aurum for gold, Ag – argentum for silver, Na – natrium for sodium, the list goes on…), the symbol K is actually derived from kali, from the root word alkali, derived from the Arabic al-qayah - ‘plant ashes.’ Although one may think an Arabic chemist was responsible for nomenclature, it was in fact German chemist Martin Klaproth who discovered potash in the minerals lepidolite and leucite – not just plants, as previously believed. Klaproth thus concluded that it ‘can no longer be viewed as a product of growth in plants,’ establishing potassium as a new element and proposing the name…kali [7]?

French chemists of the time called bestowed the name potasse onto potassium salts, rather than the element potassium itself. Deciding the name ‘potash’ would not find acceptance amongst German scientists as ‘the etymological derivation of it is faulty’ [7], Klaproth proposed calling the element kali. British chemist Humphry Davy produced potassium via electrolysis in 1807, and in 1809 Ludwig Wilhelm Gilbert proposed that Davy’s potassium be called Kalium in German nomenclature, reinforcing support for a Germanic name [8].

Interestingly, Swedish chemist Berzelius’ 1813 publication in Thomas Thomson’s Annals of Philosophy initially follows Davy’s atomic symbol nomenclature, abbreviating potassium as Po (now taken by polonium) - but merely a year later (1814) advocated for the elemental name kalium, alongside the chemical symbol K [9]. French chemists Gay-Lussac and Thénard (who also investigated the alkali metal) named potassium métal de potasse [10].

English and French-speaking countries henceforth adopted Davy, GayLussac and Thénard’s potassium, while Germanic countries remained in favour of the kalium proposed by Klaproth and Gilbert [10]. Regardless, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has designated the elemental name potassium and the official chemical symbol of K – a middle ground of some kind [12].

Tungsten - W

The name tungsten is somewhat unimaginative. Named for its heftiness (with an atomic number of 74 on the periodic table), tungsten is derived from Swedish: tung meaning heavy, and sten meaning stone [4]. Tungsten was first found in the minerals wolframite and scheelite (CaWO4 ), and first isolated as a pure metal from the former [12].

The high density of scheelite led Torbern Bergman to believe that it contained the alkaline earth baryta, but he found instead an acidic oxide now known to be tungsten oxide [12]. Wolframite has been known in written history since at least 1556 (as lupi spuma) [13], but it was some time before the element could be isolated from its mineral matrix.

The Latin name lupi spuma translates to German as wolf rahm, meaning ‘wolf’s foam;’ the frequent co-occurrence of the mineral with casserite (also known as tin-stone), leading to apparent tin ‘eating’ during extraction, much like the way a wolf devours a sheep – and thus, the name wolframite came into existence [13].

It was not until 1783 that the pure metal was isolated, when Spanish chemist Juan José de Elhuyar y de Zubice and his younger brother Fausto de Elhuyar y de Zubice, reduced tungstic acid with high heat and powdered charcoal. Despite speaking Spanish (a Romance language), they claimed the Germanic name volfram:**

“We will call this new metal volfram, taking the name from the matter of which it has been extracted…. This name is more suitable than tungust or tungsten which could be used as a tribute to tungstene or heavy stone from which its lime was extracted, because volfram is a mineral which was known long before the heavy stone, at least among the mineralogists, and also because the name volfram is accepted in almost all European languages, including Swedish.”

The name wolfram was originally put forth by IUPAC, but Swedish-originating tungsten became popular amongst English-speakers. Other Germanic languages have adopted cognates of wolfram – wolfraam in Dutch, volframas in Lithuanian, volframi in Finnish. Ironically, the element is now most commonly called volfram in Swedish, and tungsteno in Spanish!

I will admit, I’m usually a defender of names that I have been accustomed to using (Exhibit A of the aforementioned human bias), but I will say that - in this case - I’m not on tungsten’s side. Perhaps it’s because ‘heavy stone’ isn’t as creative a name as ‘wolf’s cream’ (and, well, there are plenty of heavier elements than tungsten), or perhaps it’s because the de Elhuyar brothers ought to have the honour of naming the element they discovered. IUPAC and the scientific community have still been debating about Wolfram vs. Tungsten as recently as 2005 [14] - but regardless, we’ve had to settle for the name of tungsten, and the ghost of wolfram in the chemical symbol W for now.

Conclusion

This article has barely scratched the surface of the history of elemental naming, but to fully explore every element and the drama and history behind etymologies of all name variations would be a bit too much for this magazine, let alone this article. In saying that, understanding just some of the meanings behind chemical names (not just the unusual ones!), adds a richness to scientific convention that we perhaps take for granted.

Notes:

*While mercury is the only element to retain its alchemical planetary name, other elements do bear names derived from planets and other celestial bodies; for example, neptunium (Np), uranium (U), plutonium (Pu), tellurium (Te), and cerium (Ce). For more, see reference [4].

** The letter W did not exist in the Spanish alphabet until 1914, hence volfram instead of wolfram.

Latin and its ties with Biological Classification

Many sources consider Latin a ‘dead language’ as there are no native speakers alive today [15-16]. By native speaker, I mean an individual born in Italy whose first language is Latin. However, Latin is still consistently used in Western medicine and science. Specifically, in this portion of the article, I refer solely to the official use of Latinised names in categorical biology. Why do we still use this Latin system if only a small percentage of the global population is actually fluent in Latin? Of course, having a global classification system for every organism is extremely useful. Nevertheless, it seems unproductive to utilise a dead language for this role.

Let us begin our analysis with the Latinised species name most familiar to us: Homo sapiens. (Of course, I had to italicise that name because, for some reason, it simply HAS to be like that. Anyways.) According to the Elementary Latin Dictionary of Tufts University, Homo translates to being, man, or person. It is amusing that the ‘being’ translation infers that other organisms are not ‘beings’. Sapiens translates to ‘wise’ or ‘being able to discern’ [17]. Similarly, this infers that other animals of the genus homo are not able to discern. If you speak to a modern biologist, they will tell you that, yes, most, if not all, apes do have intelligence and are able to recognise objects [18]. Moreover, all living organisms are technically ‘beings’ as they exist. Why is it that in a discipline where we know these facts to be true, we still use the term Homo sapiens to formally describe the human species?

We have one particular scientist to blame for the popularisation of using Latin to classify species. I am, in fact, referring to Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeus had already been taught Latin at a young age. Therefore, he found it appropriate to start describing species in Latin before developing the binomial nomenclature system [19]. Additionally, Latin was known as the Lingua Franca of the European scientific community up until the 18th Century. In other words, Latin was the preferred language when it came to naming scientific classifications [20].

Wrens (Troglodytes Troglodytes Troglodytes) image by Amee Fairbank-Brown from Unsplash

By writing his book Species Plantarum, Linnaeus cemented Latin as the official language by which to scientifically classify species [21].

Whilst we are currently restrained by this Latinised system, humans have still found ways to create strange and humorous species names. For example, the Eurasian wren bird species is part of the family Troglodytidae. This is simple enough, right? This is until you examine the species name for this bird: Troglodytes troglodytes. On top of this, there are 28 Eurasian wren subspecies, with one being formally known as Troglodytes troglodytes troglodytes [22]. The word troglodyte originates from the Latin word troglodyta, which roughly translates to “cave-dwelling people” [23]. Eurasian wrens are associated with troglodytes not because they are cavedwellers but because they like to live and nest in rock crevices [24]. The subspecies name Troglodytes troglodytes troglodytes is known as a triple tautonym. Other officially used triple tautonyms include Bison bison bison (Plains bison), Gorilla gorilla gorilla (Western lowland gorilla), and Giraffa giraffa giraffa (South African giraffe).

Even though the lingua franca of the scientific world today is English, it looks like we will not soon be discontinuing the tradition of using Latin names for formal biological species classification [25]. One could take the perspective that this is a unique way that humans value the history of their ancestors. With Te Reo being more frequently used in naming and referring to native NZ species, adding indigenous naming to a traditionally Western system could be a great combination of cultures and values.

[1] D. M. Guharay, A brief history of the periodic table, https://www.asbmb.org/ asbmb-today/science/020721/a-briefhistory-of-the-periodic-table#:~:text=In%20 1869%2C%20Russian%20chemist%20 Dmitri,group%20he%20would%20 rearrange%20them. (accessed Aug. 1, 2023).

[2] “Mercury,” Encyclopædia Britannica, https:// www.britannica.com/science/mercurychemical-element (accessed Aug. 1, 2023).

[3] O. Raubenheimer, “The History of Mercury,” The Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (1912), vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 445–447, 1918. doi:10.1002/ jps.3080070513

[4] V. Ringnes, “Origin of the names of Chemical Elements,” Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 66, no. 9, p. 731, Sep. 1989. doi:10.1021/ed066p731

[5] W. Lefèvre, “The Méthode de nomenclature chimique (1787): A document of transition,” Ambix, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 9–29, 2018. doi:10 .1080/00026980.2017.1418233

[6] H. Davy, “I. The Bakerian Lecture, on some new phenomena of chemical changes produced by electricity, particularly the decomposition of the fixed alkalies, and the exhibition of the new substances which constitute their bases; and on the general nature of Alkaline Bodies,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 98, pp. 1–44, Jan. 1808. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0001

[7] M. Klaproth, “Nouvelles données relatives à l’histoire naturelle de l’alcali végétal,” in Memoires de l’Academie royale des sciences et belles-lettres depuis l’avenement de Frederic Guillaume II [-Frederic Guillaume III] au trone, Paris: Academie royale de chirurgie, 1798, pp. 9–13

[8] H. Davy, “Ueber einige Neue Erscheinungen Chemischer veränderungen, welche durch die electricität bewirkt werden; Insbesondere über die zersetzung der feuerbeständigen alkalien, die Darstellung der neuen Körper, Welche ihre Basen Ausmachen, und die Natur der Alkalien überhaupt,” Annalen der Physik, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 113–175, 1809. doi:10.1002/andp.18090310202

[9] J. J. Berzelius, in Försök, att, Genom Användandet af den electrokemiska theorien och de kemiska proportionerna, grundlägga ett rent Vettenskapligt System För Mineralogien, Stockholm, 1814, p. 87

[10] P. van der Krogt, “Kalium Potassium,” Elementymology & Elements Multidict, https://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element. php?sym=K (accessed Aug. 2, 2023).

[11] A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson, Compendium of Chemical Terminology: IUPAC Recommendations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

[12] M. E. Weeks, Discovery of the Elements. Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education, 1968.

[13] P. van der Krogt, “ Wolframium (Tungsten),” Elementymology & Elements Multidict, https://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element. php?sym=W (accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

[14] P. Goya and P. Román, “Wolfram vs. Tungsten,” Chemistry International -- news magazine for IUPAC, https://publications.iupac.org/ ci/2005/2704/ud_goya.html (accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

[15] R. Risselada, Amsterdam Studies in Classical Philosopy, Vol. 2: Imperatives and other Directive Expressions in Latin, a Study in the Pragmatics of a Dead Language, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1993.

[16] G. Inglese, “Anticausativization and basic valency orientation in Latin,” in Valency over Time, Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 2021, pp. 133-168.

[17] C. T. Lewis, An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York, NY, USA: American Book Company, 1890.

[18] A. Seed, N. Emery and N. Clayton, “Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: A Case of Convergent Evolution?,” Ethology, vol. 115, no. 5, Apr. 2009, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1439- 0310.2009.01644.x

[19] D. Black, Carl Linnaeus Travels, New York, NY, USA: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979, pg. 8.

[20] M. Paterlini, “There shall be order: The legacy of Linnaeus in the age of molecular biology,” EMBO Reports, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 814-816, Sept. 2007, https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1038/sj.embor.7401061

[21] C. A. Stace, Plant Taxonomy and Biosystematics, 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kindom: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

[22] F. Albrecht et al., “Phylogeny of the Eurasian Wren Nannus troglodytes (Aves: Passeriformes: Troglodytidae) reveals deep and complex diversification patterns of Ibero-Maghrebian and Cyrenaican populations,” PLOS ONE, vol. 15, no. 8, pg. E0238206, Mar. 2020, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal. pone.0230151

[23] J. A. Jobling, The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm, pg. 391.

[24] H. F. Witherby, F. C. R. Jourdain and N. F. Ticehurst, Handbook of British Birds. Vol. 2: Warblers to Owls, United Kingdom: H F & G Witherby Ltd, 1943, pp. 213–219.

[25] C. Tardy, “The role of English in scientific communication: lingua franca or Tyrannosaurus rex?,” Journal of English for Academic Purposes, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 247-269, Jul. 2004, https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/abs/pii/S1475158503000717

Cindy is an Honours student studying chemistry. She is interested in sustainability, green chemistry, and getting 9.5 hours of sleep. Having taken Latin in high school, she knows a little bit but is nowhere near fluent, and is grateful that she has something to kinda contribute her meagre Latin towards.

Cindy Yi - BSc(Hons), Chemistry

Jasmine is a third-year Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student specialising in Ecology. She is interested in researching areas in insect ecology and ecological restoration. This year she is also a part of the Science Scholars programme.