The Fashion Industry: Not as Green as it Seems!

Fashion and Sustainability | Sienne Chan

Textiles are an integral part of our lives, especially in the form of fashion pieces. However, there is a large information gap in the fashion industry. Do we really know where and how our clothes are made? The heavy pollution that results from textile production is one of the many environmental impacts that we will be focusing on in this paper, along with recommendations on what can be done to reduce the overall negative impacts.

We hear much about saving the planet by changing what we do - ride a bike, recycle our bottles, use less plastic... but we can go further. The true impacts of what we buy have largely been ignored. As Daniel Goleman, a renowned psychologist, once said, “Our world of material abundance comes with a hidden price tag. We cannot see the impacts of the things that we buy and use daily – the toll on the planet, on consumer health, and on the people whose labour provides us our comforts and necessities.” [1]. Nevertheless, the fashion industry’s status as the most polluting sector in the world also means it has the highest potential for radical change.

This study explores the multi-layered environmental impacts of the textile industry by means of a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), including elements of consumer transparency. Various factors that contribute to consumer choices such as the environmental, economic, and social aspects that result in sustainability issues in the fashion industry are also discussed.

Figure 1: World fibre production 1980-2025 [2], [6].

With global increases in wealth and development, coupled with the widespread use of social media, many people have been influenced by the disease of consumerism. Rising consumption and increasing efficiency in production have driven the price of clothing ridiculously low [2]. The culture of buy-and-chuck-aside has resulted in immense negative impacts on the environment, with textile production and waste increasing tremendously over the past two decades (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 3: Global supply chain of textiles categorised into key stages of sourcing materials, manufacturing, and retailing, as well as the major consumers in the fashion industry [2].

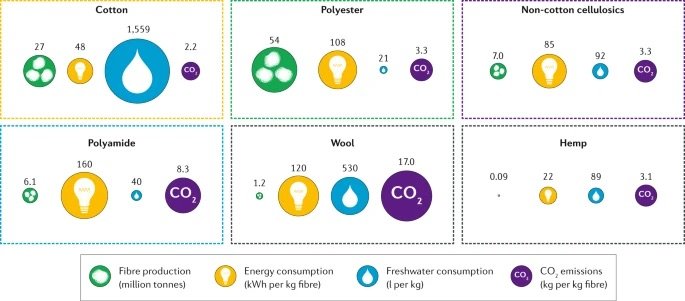

Figure 4: Environmental impacts of six different types of clothing fibres [2].

Figure 2: Textile waste infographic. Source: TheRoundup.org.

“Green” is a Mirage

In a society where being “green” is highly praised, we often aim to practise a “greener” lifestyle - choosing local produce, using public transport etc. However, not much attention is paid to the most basic necessity - clothing. A T-shirt that reads: 100% Organic Cotton: Eco-Friendly Product is a claim that is both right and wrong. Yes, cotton might seem “greener” due to its higher biodegradability than synthetics like polyester, but it also requires large amounts of water to produce. Approximately 2700 litres of water is required to grow the cotton for one T-shirt; the Aral Sea was reduced to a desert due to irrigation demands from local cotton farms [1]. The label on the T-shirt is an example of “greenwashing”, highlighting one or two virtuous attributes that persuade consumers to purchase a product, while hiding its adverse impacts.

Deconstructing the entire production process of a garment into its constituent parts is the only way to measure all its impacts on nature, from the initial production to eventual disposal. This is known as the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA).

The fashion supply chain constitutes a worldwide dispersion of subsequent operations, covering many industries from manufacturing, shipping, and retail, to agriculture (for natural fibres) and petrochemicals (for synthetics) [2]. As a result of the global shift in textile production to nations with lower labour costs, many developed countries have seen significantly reduced production, while the supply chain continues to decrease in transparency [2]. Figure 3 reveals the four major environmental impacts of textile production, with energy consumption being the most ubiquitous throughout the production process, while Figure 4 exhibits a comparison between 6 of the most commonly used fibres. Traditionally, garments have been transported by shipping containers, but more and more are being shipped by air cargo to save time, particularly with online purchases. Moving just 1% of clothing shipping from ships to air cargo results in a staggering 35% rise in carbon emissions [2]. In addition, the globalisation of the fashion industry has resulted in an uneven distribution of environmental impacts with developing countries (manufacturers) having to bear the brunt for developed countries (consumers).

The Chemical Stew

Global fibre production has doubled in the last two decades [4], making it one of the biggest industrial polluters worldwide. Fibres can be divided into two categories: natural and synthetic, where natural fibres include cotton, wool, silk and animal skins (eg. leather), while synthetics are man-made, such as the widely-used polyester, nylon and elastane. Current fibre production is dominated by synthetic fibres (~ 69%) with the remaining 31% being natural fibres and blends of both types [4]. The rise in synthetics poses an environmental concern, not only due to their lack of biodegradability but also the heavy use of chemical agents in their production that increase micropollutant levels in waterways. The rise of zinc (Zn), mercury (Hg), sulphide, sulphates, phosphates, copper (Cu), and nickel (Ni) in water bodies negatively impacts both aquatic biodiversity and human health [5]. Moreover, their heavy reliance on fossil fuel extraction further exacerbates environmental damage, with the production of synthetic polymers estimated to utilise 98 million tons of oil annually [4]. Processing fibres into textiles utilises further chemicals in the steps of bleaching, dyeing, straightening, wrinkle reduction, fire-proofing, and so on [6]. The effluent that is now saturated with dyes, de-foamers, bleaches, detergents, optical brighteners, equalisers [6], and other chemicals pollute the surrounding areas with its emission of air pollutants and residue, despite possible wastewater treatment. Particulate matter such as nitrogen, sulphuric oxides, and volatile organic compounds are among many atmospheric pollutants released [7]. Formaldehyde is widely used as a glueing agent and softener in fabrics. However, it can also cause eye-itching, irritation, and other allergies. Despite this, it is still used in clothing, though some limits are imposed on the amount used in various clothing types (eg. <30 ppm for toddlers) [7]. Finally, textile sludge composed of micronutrients, pathogens, and heavy metals results in nutrient oversaturation issues in surrounding water bodies.

Power of the Media

The popular retailer H&M had $4.3 billion USD worth of unsold clothing items in 2018 as a result of the rapid fast fashion industry [8]. This generates large amounts of textile waste, as only 15–20% is recycled annually, while the other 75–80% is deposited in landfills or incinerated [8]. In 2015, the US was responsible for the exportation of over $700 million USD worth of used clothing. This affected markets in African and Asian countries, which were subjected to massive clothing dumps, leading some of these countries to ban these imports [8].

In this era of high-speed internet and social media platforms, influencers are the dictators of fashion trends. Increasing clothing demand is driven by a decrease in prices and a rapid growth of social media influence, leading to fast fashion [8]. Consumer behaviour is strongly affected by media marketing and advertising, but rather than giving in to enticing clothing haul videos that offer alluring discounts, we can instead choose to advocate for reduced consumption and slow, sustainable fashion.

Achieving a Virtuous Cycle

As we all know, the Three Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) are the backbone of being sustainable. As a consumer, wearing hand-me-downs or even simply wearing one’s clothes until they break already does the environment a big favour by not constantly adding to the ever-growing textile waste. Reduced consumption, saying no to fast fashion, and recycling old fabric also largely reduces individual environmental impacts. As consumers are the main drivers of the fashion industry, collective consumer action on a global scale can potentially drive corporations to implement higher environmental and work standards in textile production. Thrifting is a sustainable alternative that is currently gaining traction in the younger communities, allowing clothes to be reused and recycled while reducing mainstream overconsumption. Finally, purchasing from ethical and sustainable brands instead of fast fashion can make an impact by allowing a push towards sustainable fashion.

Overall, consumer education and awareness is an area that should be expanded in order to increase positive impacts on the fashion industry.

At an industrial level, the business model has to be switched from linear to circular. Rather than operating in a linear fashion (Figure 5), the addition of a recycling step can transform the clothing production process into a more sustainable system (Figure 6). By recycling old materials, we can largely benefit from waste and pollution reduction.

Figure 5: The life cycle model [3].

Figure 6: Circular fashion business model [9].

Challenges to Sustainability

Fast fashion has been the go-to for many people due to its low prices and availability. Most challenges to sustainability as a consumer are largely economical, as many would choose to buy the cheaper product when two similar products are compared. Social aspects also include the need to feel included in the newest trends, as influenced by social media and those who buy into fast fashion. Additionally, the information gap between manufacturers and consumers plays a huge role. As previously mentioned, “green” products may not be as “green” as they seem, and many consumers are tricked into the mirage of false sustainability. Radical transparency is thus imperative in the fashion industry, to allow consumers their right to decide which cause they support. Of course, this is often met by push-back from manufacturers desiring profit. Fortunately, online platforms like Good On You allow consumers to see sustainability ratings on various brands, bringing us one step closer to sustainable and ethical fashion.

Conclusion

The proliferation of rapid production and consumption of textiles has given rise to significant environmental and climate impacts. However, the implications of increasing consumer awareness of global climate change and human injustice will be far-reaching. Ultimately, radical action by corporations will be crucial. Corporations could (1) phase out toxic substances or those which release microfibers, (2) narrow supply chains, and (3) improve textile waste management through recycling [4]. By shifting the system from linear (take, make, dispose) to circular with the approaches of narrowing (efficiency), closing (recycling), and slowing (reusing), we can largely reduce major environmental impacts [2]. Consumers can also play a part in the last two steps of this circular system. Lastly, in addition to demanding better work conditions, conscious decision-making is the key to reducing the overflowing textile waste in landfills. Yes, the boycott of fast fashion is making a stride in current news, but there is still much to be done.

“You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

- Jane Goodall

[1] D. Goleman. Ecological intelligence: The Coming Age of Radical Transparency. Penguin. 2010.

[2] K. Niinimäki, G. Peters, H. Dahlbo, P. Perry, T. Rissanen, & A. Gwilt. The environmental price of Fast Fashion. Nature Reviews Earth; Environment, 1(4), 189–200, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

[3] H. Baumann, & A.-M. Tillman. The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to LCA: An Orientation in life cycle assessment methodology and application. Studentlitteratur. 2004

[4] X. Chen, X., H. A. Memon, Y. Wang, I. Marriam, & M. Tebyetekerwa. Circular economy and sustainability of the clothing and textile industry. Materials Circular Economy, 3(1), 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42824-021-00026-2.

[5] T. Sarwar, & S. Khan. (2022). Textile industry: Pollution Health Risks and Toxicity. Sustainable Textiles: Production, Processing, Manufacturing; Chemistry, 1–28, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2832-1_1

[6] M. Koszewska. Circular economy — challenges for the textile and clothing industry. Autex Research Journal, 18(4), 337–347, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/aut-2018-0023

[7] E. Priha. Are textile formaldehyde regulations reasonable? experiences from the Finnish textile and clothing industries. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 22(3),

243–249, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1006/rtph.1995.0006

[8] K. Bailey, A. Basu, & S. Sharma. The environmental impacts of fast fashion on water quality: A systematic review. Water, 14(7), 1073, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14071073

[9] H. Lane. Circularity in fashion. Redress Design Award. https://www.redressdesignaward.com/academy/resources/guide/circularity-in-fashion. 2022.

Sienne is from the Garden City, also known as Singapore. In addition to her blazing passion for the natural sciences, she also has a soft spot for mystery novels and dabbles in creative writing.